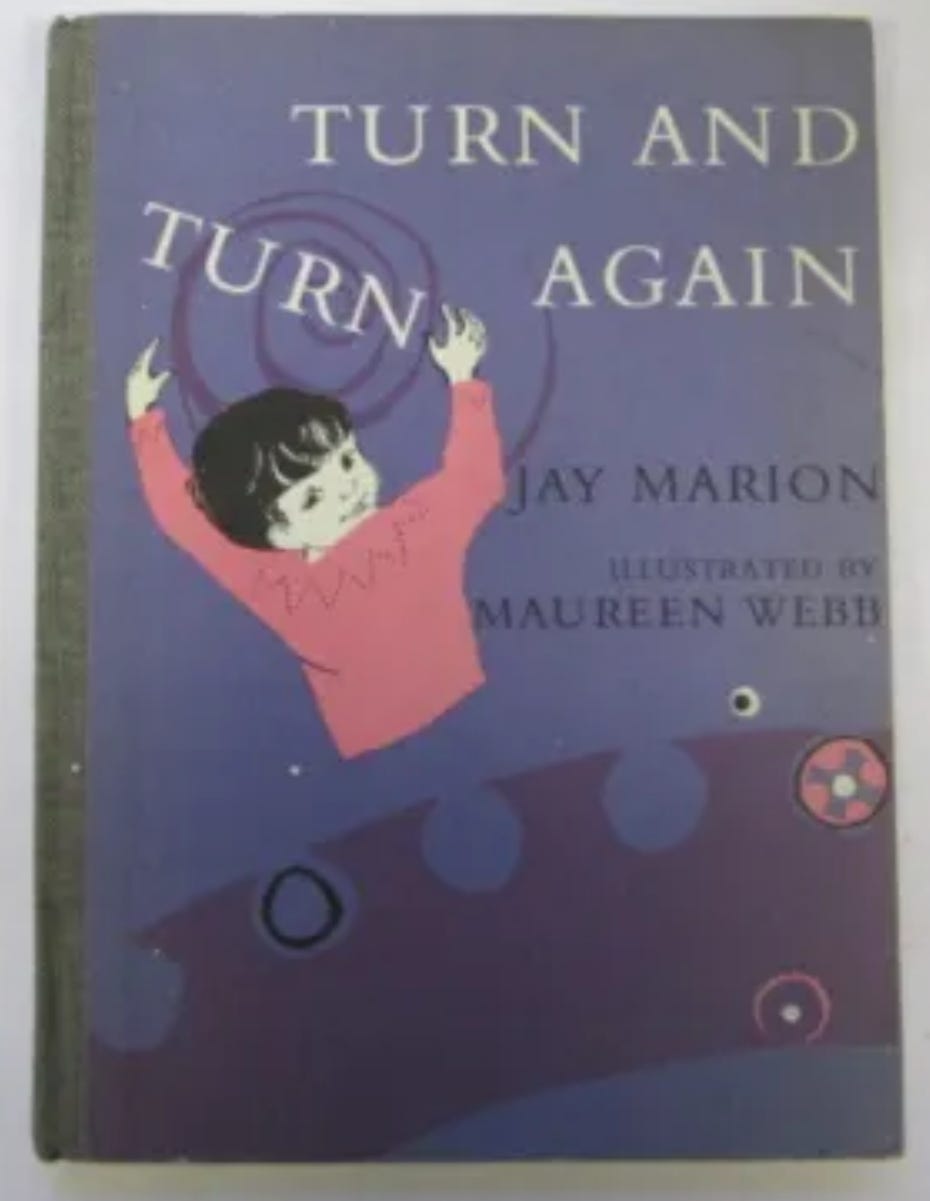

A couple of days ago I took receipt of a book. Turn and Turn Again by Jay Marion, illustrated by Maureen Web. First published in 1966, the year of my birth, it cost 18 schillings. It had sat on my childhood bookcase ever since I could remember. I don’t remember it being bought, it was always just there. I bought it again after a churn of memory and the longing of reminiscence. I had even had this book in my possession up until around seven years ago, when I decided to rid my self of many possession in a slightly misguided minimalism stage. (Aside - I don’t regret most of what I got rid of, but some items I have begun to seek out and buy again, mainly books and vinyl LPs. I don’t really understand why my thinking changed or why. It was a stage in my life and maybe one day I will write solely about that, or maybe I won’t.)

One of the young adults who live in my house was explaining quite excitedly about the joy of flicking switches and it reminded me of the book. I loved that book as a child. I remember exactly where it sat on the bookcase. On the second to bottom shelf along side all the other children’ books. The bookshelf was hand made by my father, rustic but functional, you wouldn’t want a posh bookcase in an 200 year old Kentish cottage anyway. It was stained a deep brown and went from ceiling to floor as wide as the staircase it sat in front of. If you sat on the bottom step the books were just at arms length and I was often to be found with my back against the steep open wooden stairs, which was stained the same colour as the bookcase and the surrounding beams, with piles of books beside me as I read until the light faded.

Turn and Turn Again is a simple book. It is about a young boy who can’t resist the urge to turn knobs and twiddle handles, and press buttons. he gets into trouble a lot as a child but ends up following his heart and works as an adult at a mixing desk at the BBC where he presses buttons and twiddles knobs for living. It is also about following your dreams and doing a job as an adult that makes your childhood heart swell with joy. At least that’s what I took from it. The illustrations are simple but evocative of the time. I can feel the scratchiness of the jumper Andrew is wearing, remember the sandals that were the only shoes we had come rain or shine, the short shorts and stripes T shirts.

My father was a self proclaimed feminist. But looking back he was the type of feminist that believed that girls could do all the things that boys could do, and should. Choosing a more typical, stereotypical feminine pursuit was frowned upon. It was fabulous for me to be good at maths and science, but art and English literature were pointless in his view, despite his love of Classical music, an ‘art’. When I choose to do English Lit, Art, and Classical Studies for A level he was disappointed, and ‘persuaded’ me to take Physics and Maths instead, despite my great reluctance, lack of enthusiasm, bad O level grades, and knowledge. He would have had me drop English for Chemistry but my mother put a stop to that. I failed Physics and Maths in the end. I just wasn’t good enough. And in so doing I also failed my father. Eventually I gained an extra A level in Art and was able to head to university. One of the first in our family to do so.

Choosing what to do was very hard. I wanted to follow my interests; photography, psychology, art, discussing it with my father again, I was told he wouldn’t support me through any degree that didn’t immediately lead to a job. Art and Photography were out. He thought Psychology was a load of old bunkum. I thought about Architecture, Journalism, Law, etc but I wasn’t really intelligent enough for them. I suggested Communications and Graphic design, I didn’t really understand what the course was, and we had no internet back then to do research, but that didn’t mater it was vetoed anyway. I couldn’t work out how to do what I actually wanted to do and be ‘supported’.

I think I got the wrong end of the stick. I knew I would get an almost full grant and the little that was lost I could cope with, but I would need to come home in the holidays and be ‘supported’ with housing, utilities, and food. If that support wasn’t going to be there, and I truly believed my father when he said what he said, I either couldn’t manage to go to uni (which I desperately wanted to do) or I had to choose a course that met his demands. I am not sure now, looking back, that was what he meant by support, nor would my mother have allowed him to kick me out of the house, but my ASD (Autistic Spectrum Disorder), RSD (Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria) brain took him to be talking extremely literally.

Oddly enough after I failed my A levels the first time round I got an offer through clearing. Brighton University wanted me to go and study Engineering. They must have been trying really hard to get girls in to STEM subjects. Even though I had failed Physics and Maths quite spectacularly they wanted me. My father was thrilled at the prospect that his girl could be an Engineer. I however, wasn’t. The thought that I would probably be the only girl on the course filled me with dread. Physics and Maths lessons had been hard enough with the sexist teachers and pupils, I was the only girl in A level Physics and was sent every lesson to get everyone coffee at the start of class and so missed the first 15 mins. And only one of two in Maths and the Pure Maths teacher really didn’t like us, and told us girls shouldn’t be allowed to do maths on a regular basis. I really didn’t want to be an Engineer. Much to my father’s chagrin I turned the course down.

Eventually I chose to be a teacher, a primary school teacher specialising in English Literature. My mother and my head of studies at my 6th form stood up for me. My father wanted me to specialise in Science or Maths. When I got my first job offers he wanted me to accept the one for an age range I didn’t want to teach purely because it was for a science post. I chose a different one. He never agreed with my choice to be a teacher but he couldn’t complain. He, himself, had been teacher, it was a degree that led straight to a job (and in fact I had two job offers before I even finished college), and, in his words, it wasn’t a ‘Mickey Mouse degree’ like photography.

Unlike Andrew in Turn and Turn again, I wasn’t encouraged to follow my dreams, because they didn’t fit in with my fathers idea of feminism - girls can do what boys do and should, rather than my idea - every one is equal and should be allowed to do what ever they want even if that means they follow gender normative roles. It was only when rereading this book this week that I truly realised this.

Two years after I began my teaching degree my brother went to university to study Photography with my father’s full support. It didn’t lead to a job. He was still supported. Go figure.

for more stories, thoughts and ramblings, click the button below to be notified for my next musing.

Thanks for sharing this. It’s fascinating how a book from the past can resurface and bring back so many memories and realizations. Your reflections on navigating your dreams alongside your father’s expectations struck a chord with me. It’s interesting how time reshapes our understanding of what’s important and how those early experiences continue to influence us. That book clearly held a special place for you then, and even more so now as you revisit it 😄

I wanted to be a gardener working at a garden nursery but my father said that wasn't a job for a girl. I ended up working in various office administration roles until I was 47 when, at last, I became a professional gardener. All those years of claustrophobia, hating going to work, never settling. I should have been stronger like you but this was the 1960s when a girl just needed a job until she met the man of her dreams, married, had babies and believed her father knew what was best.